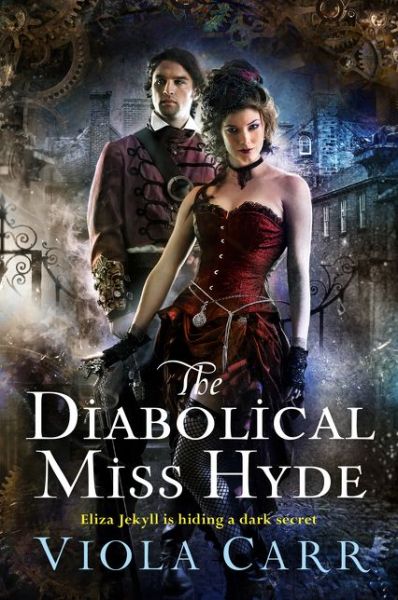

I started reading The Diabolical Miss Hyde, and in the first paragraph, I found voice. Voice is such a nebulous yet vital element in writing. It’s attitude, rhythm, dialogue. It’s what makes a book come alive. Within a matter of sentences, Viola Carr’s novel snared me because of a perspective with blunt, ungrammatical charm:

In London, we’ve got murderers by the dozen. Rampsmen, garroters, wife beaters and baby farmers, poisoners and pie makers and folk who’ll crack you over the noddle with a ha’penny cosh for the sake of your flashy watch chain and leave your meat for the rats. Never mind what you read in them penny dreadfuls: there ain’t no romance in murder.

But every now and again, we gets us an artist.

The opening narration is told in such a thick and raunchy voice that you know this takes place in the sordid underbelly of London or an equivalent. I didn’t know what a cosh was, but by golly, I knew I didn’t want my noddle thwacked. (If my pick of definitions is right, a cosh is like a police baton. Noddle is comparable to the Americanism of “noodle” for brain/head.) The writing manages to inject the right amount of unusual words to grant flavor—a fishy, grimy flavor—while not overwhelming me, as would a sing-song Cockney dialect.

Plus, there’s murder. That sets up the plot and a hundred questions right there. Whodunnit? Why? What makes this one so artistic? Cozy mysteries are great fun, but right away I know this book isn’t going to be about quaint countryside manners and quilting clubs. It’s going to be dark and drenched in gutter fluid. Mmm, gutter fluid.

Oh, but there’s more! On the second page, we get to meet another major character:

And here’s Eliza, examining the dead meat for evidence. Sweet Eliza, so desperately middle class in those drab dove-gray skirts, with her police doctor’s satchel over her shoulder. She’s a picture, ain’t she? Gaffing around with her gadgets and colored alchemy phials, those wire-rimmed spectacles pinched on her nose…

Here’s Eliza. And here’s me, the canker in her rose. The restless shadow in her heart.

The book fooled me in a brilliant way. Even though I knew by the title and back cover that this was a steampunk re-telling of Jekyll and Hyde, I wasn’t thinking of that to start. The luscious voice convinced me I was in the perspective of some street dame who watched the police investigate this artsy murder. Instead, it began with the viewpoint of Lizzie Hyde, the crude personality hidden inside the starchy Eliza Jekyll. A captive within her own body.

At that point, I was utterly hooked and happily stayed that way for the next four-hundred-some pages.

Viola Carr effortlessly switches between the first-person present tense of Lizzie (crude, passionate, strong) and the standard third-person past tense of Eliza (proper, intellectual, an everywoman) as the two halves of one woman navigate murder mysteries, political intrigues, and their own (literal) inner conflict. It’s not a technique that just anyone could handle, but it works here in a profound way. It’s dark, intense, and sometimes disturbing, and man is it awesome. You might even say… artistic.

Beth Cato is the author of The Clockwork Dagger, a steampunk fantasy novel from HarperVoyager. Her short fiction is in InterGalactic Medicine Show, Beneath Ceaseless Skies, and Daily Science Fiction. She’s a Hanford, California native transplanted to the Arizona desert, where she lives with her husband, son, and requisite cat.